A decades-long controversy over “fundamentalist” and “modernist” interpretations of the Bible came to a head in the Rhea County Courthouse in July 1925. From today’s perspective, this religious debate seems limited in scope, but in the 1920’s, the argument spilled over to touch virtually all areas of public life.

In January 1925, Representative John Washington Butler introduced a bill in the state House of Representatives to prohibit teaching, in any public school, any theory of human origin that contradicted the account of creation as recorded in the Bible. Despite some misgivings, Governor Austin Peay signed the bill into law on March 21 with a comment to the effect of “The legislature has had its say; we’ll never hear of this again.”

However, when the American Civil Liberties Union in New York learned of the law, they decided to challenge its constitutionality. They advertised for a Tennessee teacher to support the challenge, and on May 4, after the school year had ended, civic leaders in Dayton learned of the request. They recruited first-year teacher John Scopes as the defendant, even though he said he did not remember teaching the Darwinian theory.

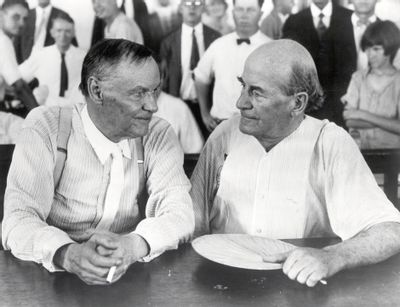

William Jennings Bryan, one of the most prominent figures in America at the time, and unquestionably the country’s foremost orator and one of the leading spokesmen for “fundamentalist” Christianity, was speaking in Memphis, Tenn., about this time. He was asked by a reporter if he would be willing to prosecute the case. He responded that he would if invited. He also was invited by the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association to represent their interests in the case.

Attorney Sue K. Hicks in Dayton issued a formal invitation to Mr. Bryan, and he accepted.

With Bryan’s entry into the case, Clarence Darrow, America’s premier defense attorney and a noted agnostic, volunteered to defend Scopes. Mr. Darrow, who campaigned for Bryan during his first presidential campaign, offered his services to the defense without charge, viewing the case as an opportunity to challenge Bryan’s religious beliefs.

On July 10, Judge John Raulston called the court into session in a packed courtroom. More than 100 reporters covered the trial, the first American trial broadcast live over a national radio network.

The state maintained that the only issue at the bar was whether Scopes broke the law, but the defense argued the law was unconstitutional. After several days of argument over the law and whether experts could testify, the judge ruled in favor of the state. He said appellate courts would be a more appropriate venue to determine the law’s constitutionality.

Blocked from offering expert testimony on science and religion, the defense called Bryan to testify as an expert on the Bible. On the next-to-last day of the trial, Darrow realized his opportunity to challenge Bryan’s religious and scientific views. For about two hours, Darrow offered what has been described as “the village skeptic’s” questions: Where did Cain get his wife? How many people were on earth 3,000 years ago? How many languages are there?”

As tempers flared, Judge Raulston cut short the examination and adjourned court until the next day.

On July 21, the defense asked that Scopes be found guilty, to allow an appeal of the case. Scopes was convicted, but the Tennessee Supreme Court in January 1927 overturned the conviction because the judge – rather than the jury – had set the fine. The court also upheld the law’s constitutionality.

The law remained on the books until 1967 when it was repealed, although no prosecution was attempted after 1925.